The Apollo Example

John F. Kennedy went before congress and publicly announced the Apollo program

and its quest for the moon.[3] NASA engineers

didn't know how to get a person to the moon back at the time of the 1961 announcement.

This needed to be studied, tested, better understood, developed and attempted.

The purpose behind JFK's announcement was to solidify the dream in the mind of

the paying voter. With that, debate regarding competing budget priorities (e.g. Vietnam)

was off the table. NASA engineers had carte blanche to focus on the challenges

in physics.

Getting a person to the moon and back requires some sort of launch vehicle,

one with sufficient thrust to lift off but not so much thrust that the occupants

don't survive. Technology was evolving swiftly.

Under a procedure of evolutionary prototyping the project entailed trying things

out, seeing what worked and what didn't, and realigning the methodology within

the overarching objective. The project was like a series of Level 2 initiatives

where formative constructions were merely fodder for learning and were promptly

discarded. Various Apollo missions were launched, some aborted. Apollo 8

encountered an unfortunate death of three astronauts. Finally, it was Apollo 11

that made its way out of Earth's orbit and off to the moon.

Performance

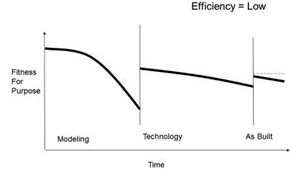

From the perspective we introduced for Level 1, and further explored for Level 2,

the trial and error learning sharply reduces the performance expectation. Invariably

the best-laid plan will encounter uncertainty, interim failures and a realignment

of performance expectations.

These initiatives are often the subject of complete re-baselining, requiring

that the project permit be reviewed with approval authorities a number of times

prior to completion.

For those

advocating a hedge factor to account for the uncertainty, the challenge here is

the implications this would pose to project motivations. If you gave the team

more money knowing the initial attempt was not practical, what would that do to

the efficiency of the spend? Rather, it appears to be a necessary requirement

to "hold feet to the fire" within reason while not unduly restricting cost growth. For those

advocating a hedge factor to account for the uncertainty, the challenge here is

the implications this would pose to project motivations. If you gave the team

more money knowing the initial attempt was not practical, what would that do to

the efficiency of the spend? Rather, it appears to be a necessary requirement

to "hold feet to the fire" within reason while not unduly restricting cost growth.

Wisdom to know how and where to adjust is only learned while the investment

is underway — much like playing chess.

If there is hedging to be done, it is perhaps privately with the approval stakeholders

as the project team acquaints them with the reality that, "notwithstanding our

promise to bring this home on time and on budget, this isn't going to happen as

submitted."

3. Kennedy, John F., Joint session of Congress, United States Government, May 25, 1961.

|